Appropriate Behavior

By

Vicki Hinze

We’ve all heard the saying, “There’s a time and place for everything.” Many of us heard that phrase often, especially in our formative years, when we were learning what behavior is appropriate under what circumstances and where—and when it was not.

Civil society—public to private (inside the family)—has always set perimeters on what is acceptable conduct and what isn’t. The facet of what’s appropriate hasn’t varied as greatly as the penalty for inappropriate behavior.

What is acceptable in some societal groups (social groups to nations) is totally unacceptable in others. How we dress, what we’re free to do (i.e., shopping, working, educational choices) or the terms under which we are free to do these things vary enormously. In the United States, far more so than in many other nations, an individual has the liberty and freedom to make personal choices. Yet we now see those choices being limited by intolerance. Whether or not people will accept these limitations remains to be seen. While we have always had the freedom to choose, we also have accepted the responsibility that comes with it. Freedom and responsibility are a package deal.

In other words, you exercise your right to choose. Others react to your choice and exercise their right to choose. We know that if we choose to exercise our right, then we must also respect the rights of those reacting to our choice. Both parties’ rights are equal, and warrant equal respect. Retaining the right to choose is also retaining the responsibility to not infringe on others’ right to choose. And when others exercise their right to choose (reaction), they also retain the responsibility to not infringe on others’ right to choose.

It’s in responsibility—not infringing—that we have gotten into the weeds. We’d rather forget that part, which is why we too often hear shout downs, shutdowns, and vitriolic opposition to marginalize, minimize, and devalue opposing opinions.

In fiction, when you marginalize, the character is invariably cast in the role of a villain. We easily recognize what the character is doing as wrong and offensive. Yet it occurs in real life and is overlooked—typically, because we agree with the opposer.

In life, some unfortunately get by with this. But in fiction, it doesn’t work. The villain is despised if not hated for his or her lack of fairness. His or her behavior is deemed unacceptable and therefore is inappropriate in the minds of readers, who demand fairness from the author and the characters to be deemed admirable or even credible. This creates the tenet for giving villains redeemable character traits or qualities.

Actions and reactions that might strike us as inappropriate often can be manipulated to be deemed appropriate by being done or said at a different time and/or place. If not wholly accepted as appropriate, others can be nudged to be more receptive to respectful disagreement.

An example. Throughout history churches have been considered sanctuaries. Hallowed ground. Even the hardest of hard soldiers engaged in battle deemed a church off-limits to assault an adversary. The reason was respect for the church and its tenets. That was a line no man of honor or worth crossed. The church was not the time nor the place to battle.

Now, leave that hallowed ground, let these adversaries meet on a battlefield, (a different time and place), and engage there, and the engagement is received by others as appropriate. In war, soldiers on opposite sides battle. If they battle in an appropriate time and place, their actions are deemed honorable.

Those who violate the protections afforded sanctuaries are deemed disrespectful, not honorable and worse. They’re given a pass on this only by those in agreement with them, and are despised for the disrespectful violations by most others.

So what does this mean in terms of contemporary fictional characters? It means the author should consider the emotional reaction to appropriate and inappropriate behavior. The author should weigh the likely reaction of the reader and structure the events and characters’ actions according to the emotional reaction the author seeks. The author should ask if the time and place and appropriate and/or inappropriate behavior best serves the story.

If the story is to be of value, its characters must be credible. Obviously, respected characters are able to carry more story weight than ones who are not. Readers must believe the character is capable of doing what s/he does in the novel. Must be logically motivated in a credible conflict and have behavior consistent with his or her actions.

It is reasonable for a taxi driver to handle a car chase with stunning feats. It isn’t reasonable or credible for a taxi driver to perform brain surgery—unless the author has established that he is a brain surgeon who, say, made a mistake and chose not to perform surgery anymore but finds he must or someone else will die. This is that person’s only chance to live, so the surgeon now taxi driver performs the surgery. Appropriate behavior that is credible and motivated. Even better, the character is conflicted, fears failure, but does the surgery anyway because he is this patient’s last hope. So he swallows his own fears and misgivings and dedicates himself, hoping to save this other person’s life.

We can make the inappropriate appropriate, or the appropriate inappropriate. We do so first by understanding the predictable emotional reaction in readers and secondly by proving (through the use of specific, concrete details) that the character engaging in behavior is acting logically and credibly. If acting for just cause, then that’s even better. Just cause injects a nobility factor that appeals. This tool enables characters to do the wrong thing for the right reason.

While there might be exceptions to the two requirements—rules are successfully broken all the time—I failed to think of one where those two requisites could be set aside and the behavior flip still worked for me. Perhaps you’ll have better luck.

In life, we know what we deem acceptable and unacceptable. By the time we become adults, we have learned the lessons about appropriate behavior as it relates to time and place. But there will always be exceptions. Some who have not yet learned those lessons, not yet learned the impact or consequences of infringing (deliberately or unintentionally) on the rights of others. And we’ll all make mistakes.

Those mistakes can be useful in fiction. They are home to the unexpected twists and turns in characters’ lives. Not that we want to experience the fallout often in real life, but it’s a useful tool for generating conflict in fiction.

Because someone will ask…

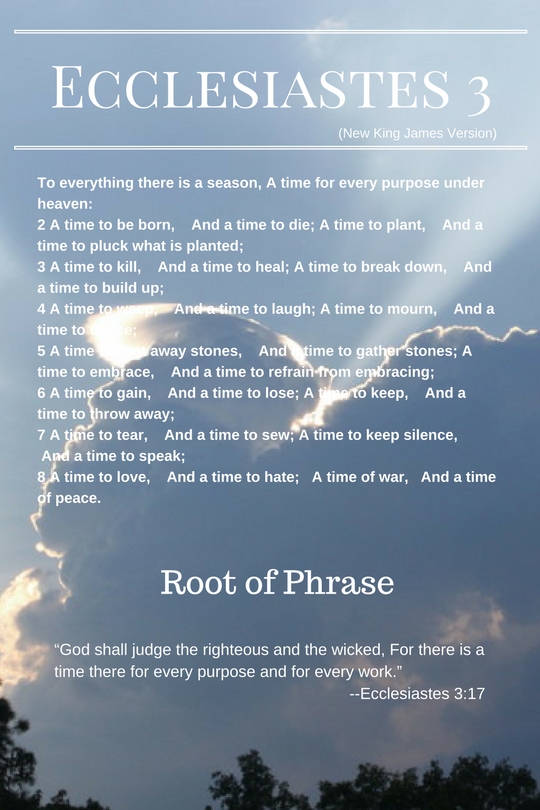

I cited the example of the church sanctuary in this article because the root of the “time and place” phrase, like so many of the quotes and phrases common in our society, comes from the Bible. So that you have the complete and direct reference, it follows:

* * * * * * *

© 2016, Vicki Hinze.  Vicki Hinze is the award-winning bestselling author of nearly thirty novels in a variety of genres including, suspense, mystery, thriller, and romantic or faith-affirming thrillers. Her latest release is The Marked Star. She holds a MFA in Creative Writing and a Ph.D. in Philosophy, Theocentric Business and Ethics. Hinze’s website: www.vickihinze.com. Facebook. Books. Twitter. Contact. KNOW IT FIRST! Subscribe to Vicki’s Monthly Newsletter!

Vicki Hinze is the award-winning bestselling author of nearly thirty novels in a variety of genres including, suspense, mystery, thriller, and romantic or faith-affirming thrillers. Her latest release is The Marked Star. She holds a MFA in Creative Writing and a Ph.D. in Philosophy, Theocentric Business and Ethics. Hinze’s website: www.vickihinze.com. Facebook. Books. Twitter. Contact. KNOW IT FIRST! Subscribe to Vicki’s Monthly Newsletter!